Methamphetamine Is Now Assaulting the Same Regions Crippled by Opioids

Ohio, once the epicenter of the opioid epidemic, is now the center of a new methamphetamine epidemic—as is Kentucky, another state that’s long struggled with opioid problems. An increase of meth and cocaine both have followed on the heels of heightened efforts to save people from opioid overdoses.

Nationally, campaigns were launched by governmental and private organizations to overcome problems created by opioid addiction, especially overdose deaths. Treatment programs across the country tailored their programs to the specific needs of those addicted to opioids. While it’s important to curtail the loss of life to opioids, focusing too strongly on a single category of addiction neglected the larger problem.

The recent upswing in methamphetamine trafficking and addiction makes it clear that focusing on one aspect of our addiction problem missed the mark. This narrowed, opioid-specific approach to helping the addicted recover doesn’t eliminate the possibility that an addicted person may simply switch from one drug to another if the supply of their preferred drug dries up.

This tunnel-vision approach doesn’t help Americans break free from all drugs. It doesn’t convince young people to steer clear of drugs. The current solutions being emphasized let other drug problems grow without restraint.

Is This Happening in Other Parts of the Country?

While our attention was rigidly focused on the death toll from opioids, methamphetamine was beginning its comeback in many regions of the country. Several years ago, meth was perhaps the biggest drug scourge this country struggled with. In small domestic labs across the landscape, meth cooks were using stolen or diverted cold medicine to mix small batches of the drug. Through greater control of cold medication supplies, these small labs were largely put out of business.

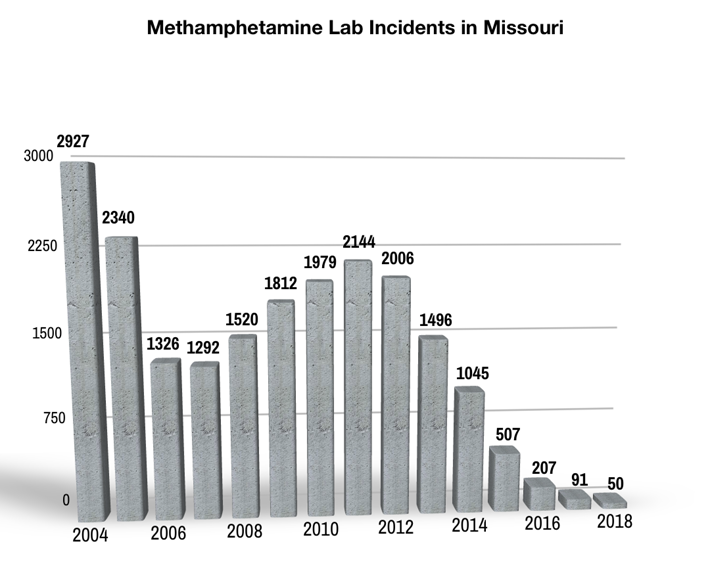

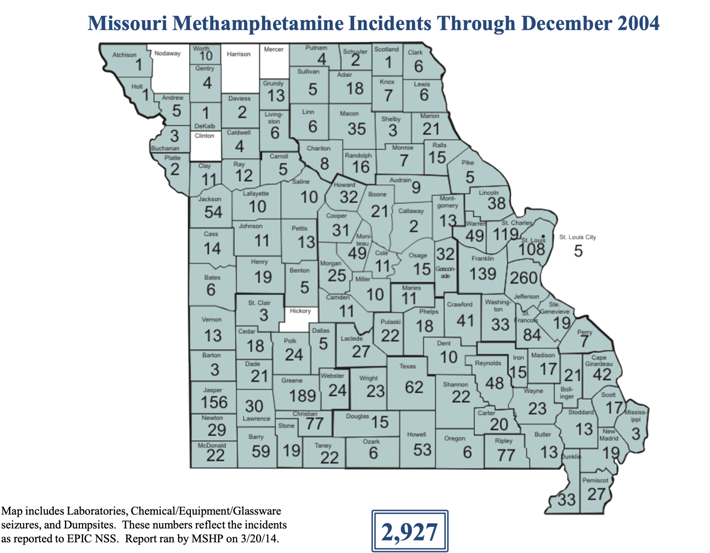

For reasons I’ve never been able to understand, Missouri was the epicenter of small methamphetamine lab production. The number of meth labs dismantled each year in Missouri alone gives you an idea of the scale of this problem when it was at its height.

In 2004, you can see the high number of labs that were found and destroyed. New legislation made cold medication harder to obtain and the number of labs located began to drop. In 2007, a new method of production was developed that required much less cold medication to create meth and the numbers began to climb again.

Check out the number of labs destroyed and meth production-related seizures in this state in 2004, the highest year on record.

But then things began to change.

Opioid Use Soared

First, the focus of drug traffickers swung around to opioids. As described in the book Dreamland The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic by Sam Quinones, new methods of illicit opioid distribution developed that meant that those addicted to opioids no longer had to drive to sketchy neighborhoods in inner cities to get a fix. Those who were addicted (including many who started by taking painkillers prescribed by their doctors) could easily obtain the fixes they needed in the suburbs or even rural areas.

The focus of the media, government and drug rehabs was soon riveted on finding solutions to the rocketing number of opioid overdose deaths.

Second, Mexican drug cartels began to work out new methods of methamphetamine production. They established new channels to acquire the chemicals they needed, usually from China. And they began to build Superlabs capable of large batches of methamphetamine of greater purity than those normally seen in the U.S. As much as 100 pounds of this deadly drug could be produced in each manufacturing cycle.

All Eyes Were Fixed on the Opioid Epidemic

And at that point, things began to change dramatically. As efforts mounted to overcome the opioid epidemic, the prescribing methods used by doctors changed. More states set up Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs to catch those going from doctor to doctor to get their pills. Some patients were simply cut off by their doctors once someone identified them as a “drug seeker.” Fentanyl entered the market and the death rate from this drug soared. Opioid users began to change their injection procedures in an effort to make sure they didn’t die. Some opioid users were scared off their drug of choice and began to look for methamphetamine.

It was the perfect time to start trafficking more methamphetamine into the country. Drug dealers and the cartels manufacturing drugs in Mexico didn’t miss a beat. They increased production and purity of the drug and sent shipments on existing channels into the U.S. More Superlabs went into operation to meet the demands of cartels who were ready to exploit this opportunity.

Finally, you arrive at a situation like this one: In 2019, state troopers in Missouri stopped a car driven by a California woman. Her passenger was a 15-year-old girl whose mother thought she was in school. The girl told troopers she had drugs strapped to her body. On investigation, troopers discovered packages of meth weighing 5.5 pounds taped to her abdomen.

Because the focus of advocates, activists, legislators, law enforcement and health professionals was riveted on opioids, we were unprepared when meth use and seizures began to increase. And increase they did.

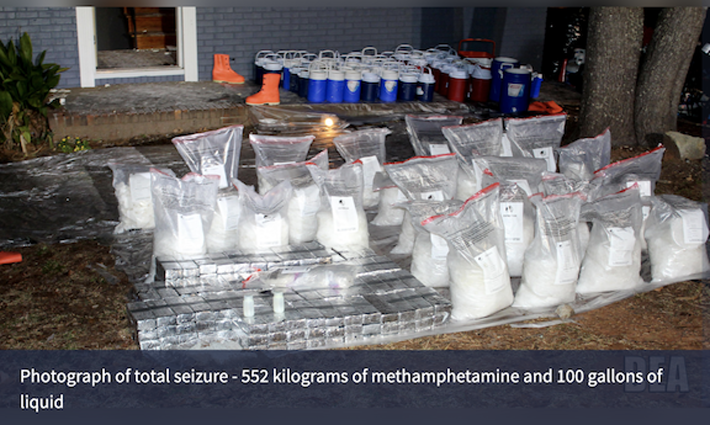

In July 2019, the Drug Enforcement Administration reported seizures averaging more than ten times the volume of 2005 seizures, each with much higher purity than in years past. In 2005, DEA agents seized 311 pounds of meth along the Southwest border. Six months into 2019, agents had seized 1,400 pounds of the drug. These new shipments were cheap, potent and very quickly reached communities all across the country.

Here’s an image from one of those seizures: 1,214 pounds of crystal meth and 100 gallons of liquid meth.

Addressing Methamphetamine

Some people refer to the phenomenon of focusing on only one drug at a time as “whack a mole,” after the carnival game where you try to hit animal heads as they pop up from hidden recesses. You whack one mole after another but there’s no end to this process. If you focus on only one drug at a time—for example, first methamphetamine, then opioids, then marijuana, then methamphetamine again—there’s always going to be another problem coming over the horizon to addict and/or kill people.

In 2017, fentanyl was the deadliest drug on the illicit marketing, causing 27,299 overdose deaths. Heroin and cocaine were in the #2 and #3 spots, and methamphetamine was in the fourth spot with 9,356 deaths. Meth often kills by overstressing the heart, causing cardiac arrests, heart attacks or destruction of the aorta. Meth very often addicts a person very quickly, and can kill just as unexpectedly.

Yes, there are specific drug emergencies that must be addressed. But it’s a mistake to allow yourself to become too focused on a set of solutions that really only applies to one type of drug. Drugs go in and out of style. A drug becomes too deadly and people shy away from it, like what is happening now with fentanyl. Or it becomes famous for its destructive effects. Drug users share their experiences and the popularity of this drug lapses, like with PCP and some types of bath salts.

When parents are talking to their children about drugs, they must make it clear that all drugs are destructive and nearly all the illicit drugs these youth will encounter are also addictive. Many are also deadly.

As an example, at one time, perhaps parents could take a tolerant view of a teen’s use of marijuana. While it was never safe to do so, it’s incredibly unsafe at the moment because of the intensely potent forms of this drug on the market. In 2019, the U.S. Surgeon General noted some of the dangerous effects of today’s cannabis products in his advisory Marijuana Use and the Developing Brain, as follows:

- Increased rates of school absence and drop-out, as well as suicide attempts.

- Risk for and early onset of psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia, which increases with frequency of use and potency of the marijuana product.

- Changes in the areas of the brain involved in attention, memory, decision-making, and motivation.

- Deficits in attention and memory have been detected in marijuana-using teens even after a month of abstinence.

- Impaired learning in adolescents. Chronic use is linked to declines in IQ, school performance that jeopardizes professional and social achievements, and life satisfaction.

The upshot is this: All illicit drug use and prescription drug misuse is dangerous and usually addictive. Nearly all drugs can be deadly at the right dose.

When we are fighting the drug problem and trying to save lives, it’s important to not forget these facts. If you’re involved in implementing solutions, try to not let yourself get tunnel vision related to any single aspect of the larger problem.

Any drug rehabilitation program, to be truly successful, must help a person return to a stable, fully sober condition with life skills sufficient to deal with the ups and downs of life. Otherwise, they are at risk of craving a high so much, that even if they are being treated with Suboxone, they may look for some other drug to satisfy their cravings. As reported in a 2012 analysis from the State of Ohio, “Suboxone is used in combination with alcohol, crack cocaine, marijuana, powdered cocaine and sedative-hypnotics.” And now, possibly methamphetamine.

Sources:

- https://www.cincinnati.com/story/news/2020/02/13/meth-opioids-new-epidemic-of-addiction/4551991002/

- https://www.mshp.dps.missouri.gov/MSHPWeb/Publications/Reports/2004StatewideLabIncidents.pdf

- https://www.narconon.org/drug-information/methamphetamine/

- https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4440680/

- https://www.dea.gov/stories/2019/07/10/methamphetamine-seizures-continue-climb-midwest

- https://www.dea.gov/press-releases/2020/02/20/dea-announces-launch-operation-crystal-shield

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_12-508.pdf

- https://www.narconon.org/drug-information/pcp.html

- https://www.narconon.org/drug-abuse/signs-symptoms-bath-salts.html

- https://www.narconon.org/drug-information/marijuana/

- https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/reports-and-publications/addiction-and-substance-misuse/advisory-on-marijuana-use-and-developing-brain/index.html

- https://mha.ohio.gov/Portals/0/assets/ResearchersAndMedia/Workgroups%20and%20Networks/OSAM/DrugTrendReports/2012-Jan-Drug-Trends-Full-Report.pdf

®

®