Fentanyl Today: An Update on this Deadly and Ever-Changing Phenomenon

The drug problem in America is like a vast, seething, writhing python. It is never still. It changes every moment:

The drugs being trafficked change.

The patterns of getting drugs into this country change.

The source countries change.

The demographics of drug use and addiction change and the types of drugs causing death change.

Keeping up with this monstrous situation requires constant vigilance if we are to track the trends as they change. To some degree, it is necessary to keep abreast of the changes if one is to correctly allocate resources to alleviate the worst effects of this plague. And fentanyl is perhaps the worst of the worst, the most deadly drug to ever land on our shores.

What is Fentanyl?

It’s a fast-acting synthetic opioid. It’s been used medically for nearly sixty years. After many years of legal use, it has begun to be manufactured in illicit labs, primarily overseas.

Medically, it’s administered intravenously, as a skin patch and as a slow-dissolving lozenge. It is so powerful that its use has been largely restricted to cancer pain, end-of-life-pain and breakthrough pain. It is 50 to 100 times more powerful than morphine and 30 to 50 times more powerful than heroin. That makes it very easy to overdose on this drug when it is abused.

Like other painkillers, there’s always been a market for fentanyl that was stolen from medical facilities or pharmacies. A nurse could steal the fentanyl meant for patients and inject them with water, keeping the fentanyl for their own use. A healthcare worker could steal fentanyl patches from a patient’s body in a hospital or nursing home. Because of the ever-present danger of arrest, diversion from medical facilities has always been fairly limited.

In 2005, there was a surge of fentanyl-related deaths that continued until 2007. This was the first major sign of illicitly manufactured fentanyl. In this case, the deadly supply was traced to a lab in Mexico. The lab was shut down and the deaths slowed to the usual number resulting from fentanyl diverted from medical sources.

For several years after that, fentanyl overdose deaths stayed low.

Illicit Manufacturing Returns

Of course, that low level of deaths didn’t stay low forever. New players decided that they could follow the example of the Toluca labs and we had supplies of illicit fentanyl flooding into our cities.

By tracking how many different samples of fentanyl were sent to forensic laboratories, we can track the growth in the fentanyl market.

In 2010, there were 668 samples of two types of fentanyl submitted to law enforcement labs, plain fentanyl and sufentanil.

On March 18, 2015, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) issued an alert on the increasing threat from fentanyl. Their alert notes that the DEA had seen a “significant resurgence” in fentanyl seizures. In 2013, state and local labs had seized 942 samples of the drug. But in 2014, there were 5,541 seizures of fentanyl sent to forensic labs for analysis. This number kept climbing until 2019 when it reached 100,378.

Law enforcement agencies had to begin testing for and recording all the different types of drugs from the fentanyl family in these samples. According to the National Forensic Laboratory Information System, here’s the list of fentanyl and related compounds they received for analysis in just a four-month period in 2020:

- Fentanyl - 29,133

- 4-ANPP - 2,152

- Acetyl fentanyl - 806

- Phenethyl 4-ANPP - 130

- Carfentanil - 94

- Valeryl fentanyl - 89

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced that in 2018, there had been more than 31,000 deaths resulting from synthetic opioids alone—a category that included only the fentanyl family and a few deaths from the painkiller tramadol.

The worst hit state was West Virginia, where the rate of synthetic opioid-involved death was 34 per 100,000. That means that for every 100,000 people of any type, drug-using or not, 34 West Virginians died.

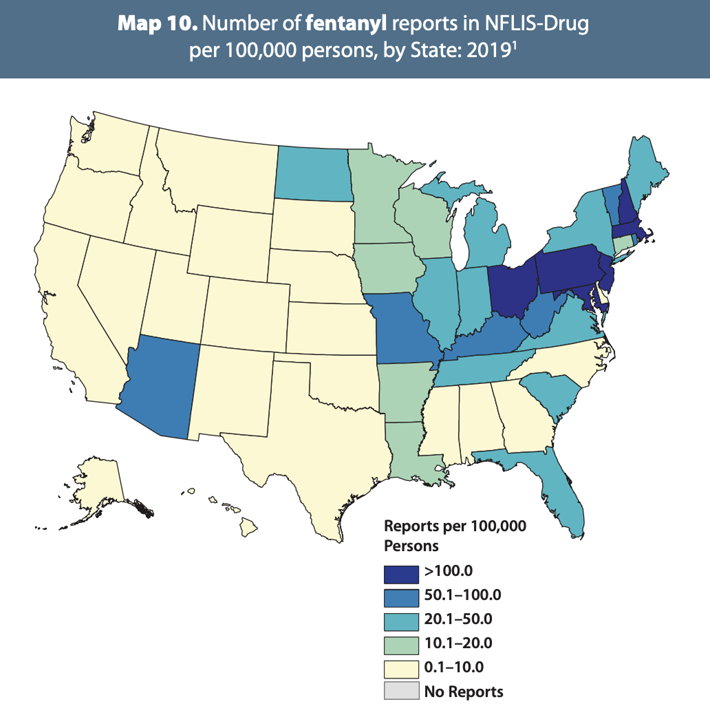

By 2019, the number of samples of seized fentanyl jumped to nearly 100,000, according to the National Forensic Laboratory Information System. Ohio alone had 17,064 seized samples of fentanyl and more than 6,000 seizures of other drugs from the fentanyl family.

The change in these numbers reveals the flood of fentanyl reaching every corner of our country.

Why Do Drug Dealers Like Fentanyl?

Drug dealers add fentanyl to give their diluted heroin more kick. Fentanyl is relatively cheap because it is synthetic—it doesn’t need a successful poppy crop in Mexico or Afghanistan.

Dealers dilute a bag of heroin with a “cutting agent” such as caffeine, an antimalarial drug, a laxative or over-the-counter painkiller. They can then mix in a small amount of a drug from the fentanyl family. They get a much larger bag of product to sell which means more profits. They then sell small bags of highly diluted heroin that has been made more potent with this small quantity of fentanyl. For the customers, it will still have plenty of potency. But because the dealers are not experts, they can mix in too much fentanyl or mix it unevenly. Then people will begin to die.

In this map from 2019, you can see that the distribution of fentanyl is heaviest by far in the Eastern U.S. But as we mentioned at the beginning of this article, the situation is changing. It never stays the same for long.

For insight into some of the changes affecting us, let’s take a look at shifts in specific area: China, Mexico, Philadelphia and the West Coast.

The Situation in China and Mexico

Once illicit manufacturing kicked into high gear once again, China and Mexico were the primary source countries for fentanyl arriving in the United States.

China has more than 5,000 pharmaceutical drug manufacturers, but according to the Rand Corporation, only a small number are monitored because there is a shortage of inspectors. Therefore it is not difficult for these manufacturers to create enough of this drug to virtually saturate the U.S. without being detected.

In 2017, China acceded to encouragement from the United States and banned the manufacture and export of four types of fentanyl: carfentanil, furanyl fentanyl, acrylfentanyl and valeryl fentanyl. This was encouraging but there are so many types of fentanyl that banning four types barely made any difference.

In 2019, China announced that it would treat all forms of fentanyl as controlled substances. But with an insufficient number of inspectors, this action may not bring this industry under control.

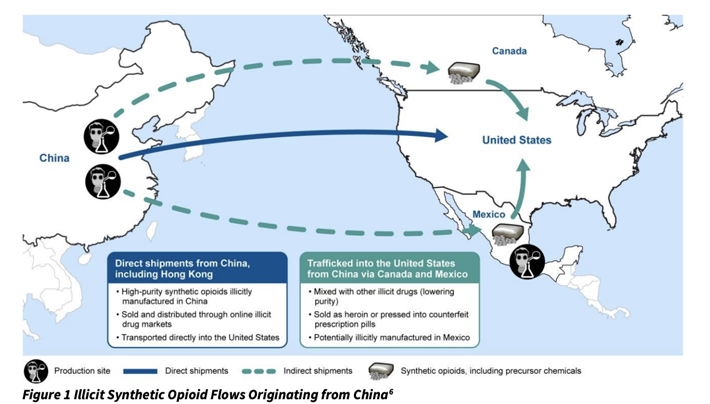

According to a report from National Public Radio (NPR), when China restricted the manufacture of all forms of fentanyl, direct shipments of these drugs fell but “nimble Chinese vendors have developed new distribution strategies by producing and selling the precursor chemicals used to make fentanyl.”

The U.S. State Department published this map showing that Chinese fentanyl travels to Canada and Mexico and then into the U.S., as well as coming direct. In the 2019 Drug Threat Assessment, the DEA states: “Fentanyl suppliers will continue to experiment with other new synthetic opioids in an attempt to circumvent new regulations imposed by the United States and China.”

NPR reports that Chinese companies are marketing their products on social media and have allied themselves with Mexican drug cartels who will buy their precursor chemicals and make fentanyl out of them. The Mexican cartels then use their existing trade routes to bring the drugs into the U.S.

In other words, as the rules change, the players change the game they are playing so they can continue their activities.

The Situation in Philadelphia

The severe drug problem in Philadelphia isn’t even an open secret. It’s no secret at all. In 2018, the New York Times ran an extensive report on the Kensington neighborhood of Philadelphia which they referred to as “the largest open-air narcotics market for heroin on the East Coast. It’s known for having both the cheapest and purest heroin in the region and is a major supplier for dealers in Delaware, New Jersey and Maryland.”

According to that report, by the summer of 2017, there was already fentanyl in the local heroin supplies. The report also notes that deaths related to fentanyl had increased 95% in the prior year.

By 2020, that situation changed some more. According to NBC, Health officials in the city reported that fentanyl was appearing in “everything.” The city released a statement that said that testing of those who died of drug overdoses found fentanyl in supplies of heroin, stimulants, hallucinogens, synthetic cannabinoids, counterfeit prescription opioids and benzodiazepines.

One of their health officials also noted that drug sales involving fentanyl had expanded out of the Kensington neighborhood and endangered anyone buying illicit drugs anywhere in the city. The number of deaths continued to increase, jumping 350% in the first nine months of 2020. Eight out of every ten deaths in the first nine months of 2020 involved fentanyl.

The New York Times article details exactly how difficult it is to eradicate a problem like this, rehabilitate all those stuck in their addictions and clean up the Kensington neighborhood. The short answer is that it is nearly impossible.

The Situation on the West Coast

For many years, the types of heroin distributed on the East Coast and the West Coast were radically different. East Coast heroin was whiteish and powdery, West Coast heroin was dark and sticky and was called “black tar heroin.” It was much easier to mix fentanyl powder in with East Coast heroin than black tar heroin, so for many years the East Coast was dealt a heavier burden of fentanyl deaths than the West Coast.

Some drug traffickers found a way to get fentanyl into black tar heroin and once again, this created a change in the number of people losing their lives to this drug. Fentanyl was also found pressed into counterfeit pills in some West Coast cities.

Between 2013 and 2018, the number of West Coast deaths increased ten-fold. The stricken locations included Arizona, California, Colorado, Texas and Washington. Partial information for 2020 available at the time of this report from Drug and Alcohol Dependence showed that the 2020’s number of deaths were likely to be 63% higher than those in 2019.

This change was definitely not in the right direction.

Our National Situation

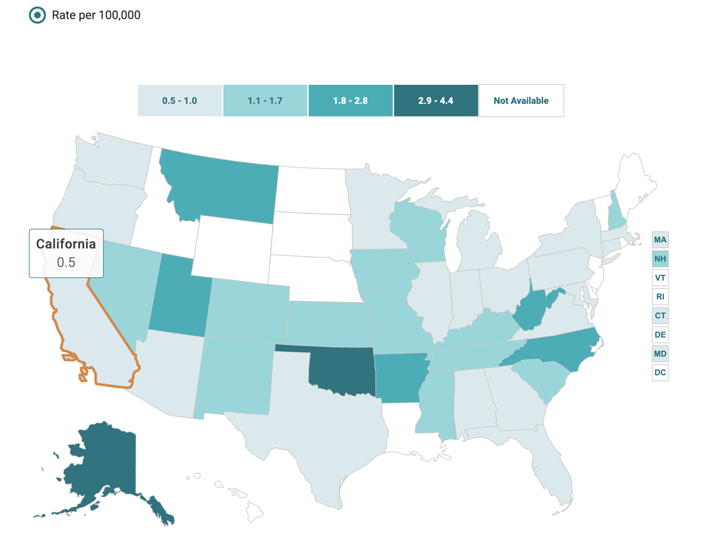

Look at these two maps from the State Health Access Data Assistance Center. The first shows the rate per 100,000 people of synthetic opioid deaths in 2009. The highest rate is in Oklahoma, at 4.4 deaths per 100,000 people.

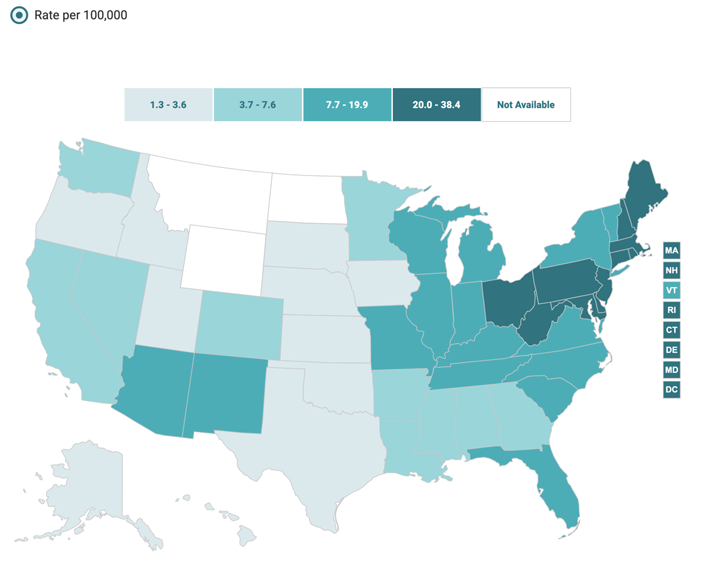

The second map is from 2019. It may not look tremendously different but check the color key. The 2009 color key tops out at 4.4. The 2019 color key tops out at 38.4, Delaware’s horrific rate of loss. The maps reveal how the order of magnitude of our loss has changed dramatically.

Now you can see the terrible increase in the number of people we are losing to fentanyl-type drugs. Again, this is another terrible change. But we must know about these changes if we are to improve these situations and dozens of others like them.

Fighting our Enemies

Synthetic opioids which, again, is a category composed primarily of drugs from the fentanyl family, are stealing our neighbors, friends and family members.

Fentanyl is a sinister enemy. It can be fought by keeping our youth drug-free, by educating our young people thoroughly on the risks of using drugs. And by inspiring our youth to be goal-oriented and helping them achieve those goals.

It can be fought by providing effective drug rehabilitation that gives a person back his or her life. And by intervening when necessary to get an addicted person into rehab.

It can even be fought by lending a helping hand to those in trouble or distress. You never know when a kind word, a hug or a patient conversation over a cup of coffee might help a person make the right decision.

There’s a hundred ways we can fight back against these drugs, against those who so thoughtlessly make them and against those who bring them to our streets. The next change and the ones after that must be in the direction of a more sober, more drug-free and healthier country.

Sources:

- https://www.jpain.org/article/S1526-5900(14)00905-5/pdf

- https://www.dea.gov/factsheets/fentanyl

- https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a605043.html

- https://www.fda.gov/inspections-compliance-enforcement-and-criminal-investigations/press-releases/november-5-2018-nurse-sentenced-taking-fentanyl-personal-use

- https://kfor.com/news/former-enid-cop-charged-with-stealing-fentanyl-patches-from-nursing-home-residents/

- https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5729a1.htm

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7521591/

- https://www.nytimes.com/2018/10/10/magazine/kensington-heroin-opioid-philadelphia.html

- https://www.nbcphiladelphia.com/news/health/fentanyl-is-in-everything-philadelphia-says-overdose-deaths-skyrocketing/2674262/

- https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/fentanyl.html

- https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/2009/June/afghanistan-identifies-cutting-agents-for-heroin.html

- https://www.rand.org/blog/2019/05/chinas-ban-on-fentanyl-drugs-wont-likely-stem-americas.html

- https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2020-02/DIR-007-20%202019%20National%20Drug%20Threat%20Assessment%20-%20low%20res210.pdf

- https://www.cnn.com/2017/02/16/health/fentanyl-china-ban-opioids/index.html

- https://www.npr.org/2019/04/01/708801717/china-to-close-loophole-on-fentanyl-after-u-s-calls-for-opioid-action

- https://www.npr.org/2020/11/17/934154859/street-fentanyl-surges-in-western-u-s-leading-to-thousands-of-deaths

- https://publichealthinsider.com/2020/06/11/fentanyl-found-in-black-tar-substances-could-lead-to-increases-in-fatal-overdose/

- https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Fentanyl-Advisory-Movement-Tab-C-508.pdf

®

®