Pharmaceutical Distributors Next in Line for Congressional Investigation

Families who have lost loved ones to the opioid epidemic should be pleased to hear that five chairmen or CEOs of pharmaceutical distribution companies have been called before Congress to account for their actions. The executives summoned were:

- Joseph Mastandrea, chairman of Miami-Luken, a drug wholesaler in Ohio

- John Hammergren, chairman, president and chief executive of McKesson, a distributor based in San Francisco

- Steven Collis, chairman, president and CEO of AmerisourceBergen, a distributor based in Pennsylvania

- Christopher Smith, former president and CEO of H.D. Smith Wholesale Drug, recently acquired by AmerisourceBergen

- George Barrett, executive chairman of Cardinal Health, a distributor in Ohio

Why has Congress chosen to intensively question these executives? Because all their companies were involved in shipping unfathomably massive quantities of addictive pills to West Virginia, fueling the widespread addiction to opioids that took thousands of lives in that state alone.

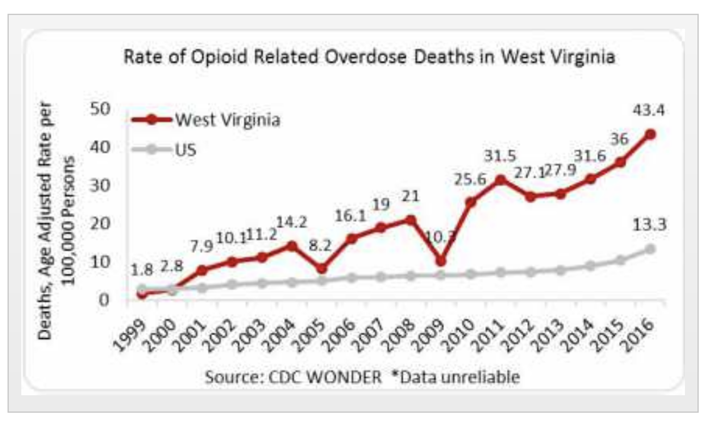

It would only take one graph to show you the disastrous effects of the opioid epidemic in this state that has the highest rate of overdose deaths in the country. This astronomical increase in the rate of opioid deaths makes it worthwhile to investigate anyone involved in providing addictive substances to this region.

According to the Washington Post, the House Energy and Commerce Committee oversight panel has been investigating the practice of pill-dumping by wholesalers. In other words, these companies sent millions of pills into towns with just a few hundred residents. Members of this committee seek to determine who placed profits far above ethics as the shipments continued. Since there are not enough residents in some of these towns to require the number of pills shipped to them, the very obvious and logical assumption is that millions of these pills were diverted to the illicit market. But these distributors took no action to curb the illicit use of their products.

Here’s some specifics on why Congress felt it was vital to investigate pharmaceutical distributors:

- In eight years, McKesson and Cardinal Health shipped 12.3 million doses of addictive painkillers to a single pharmacy in Mount Gay-Shamrock, West Virginia, population 1,235.

- In the same time period, Cardinal Health shipped 10.5 million pills to the Hurley Drug Company in Williamson, population 3,036.

- In Kermit, one pharmacy received nearly nine million addictive pills of opioids in just two years. That was 600 times the number of pills received by a nearby Rite Aid pharmacy.

- AmerisourceBergen never took action when its sales of oxycodone to Greenbrier County rocketed from 292,000 pills to 1.2 million in just one year.

- McKesson sent Mingo County (population 25,000) 3.3 million pills of hydrocodone in just one year.

These facts were enough to compel the House Energy and Commerce Committee to summon these executives to account for these actions that conveniently escaped their notice year after year.

How Did These Executives Respond to the Questions?

Not surprisingly, most of the executives deflected blame away from their companies and toward doctors, pharmacists and the Drug Enforcement Administration. There were a couple of lucid moments, however.

When asked if the executives felt their companies had contributed to the opioid crisis, one of them actually answered “Yes.” That was Joseph Mastandrea, chairman of Miami-Luken. Barrett of Cardinal Health expressed his regret that the company did not act to limit shipments to two small pharmacies. “With the benefit of hindsight, I wish we had moved faster and asked a different set of questions,” he said. “I am deeply sorry we did not. Today, I am confident we would reach different conclusions about those two pharmacies.” Is it really possible these corporations with thousands of staff never noticed this discrepancy, even though it continued for years?

According to multiple news reports, this inaction that contributed to the spread of opioid addiction and the failure of these executives to accept any meaningful responsibility infuriated the Congressmen, just like it would any feeling, caring human being.

This investigation is not yet complete. When it is, these corporations could be required to fund addiction recovery services for the millions of Americans who still struggle with addiction to painkillers or who sought out illicit drugs when their money ran out for pills. Using pharmaceutical company resources to fund recovery for these people would be justice indeed.

®

®