How to Launch an Epidemic of Addiction

Apparently, it’s ridiculously easy to launch an epidemic to any drug you choose. And it will work with not just ONE drug, but ONE DRUG AFTER ANOTHER. Addiction to many drugs can be instigated in a heartbreaking series though use of this one simple tactic.

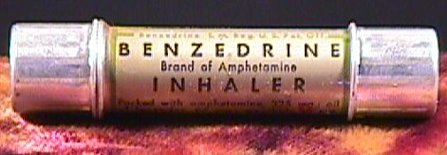

This tactic was described in a report on America’s first amphetamine epidemic, a problem that gained and retained prominence between 1929 and 1970. Increasing use of amphetamines began in the late 1920s when a Benzedrine inhaler was sold over the counter as a solution for congestion. Some people who enjoyed the energy they received from the amphetamine in this inhaler began to break open the packages and consume all the drug in one shot. They could quickly become addicted if they misused the inhaler this way.

In the 1930s, another form of Benzedrine was marketed as a remedy for narcolepsy, Parkinsonism and depression. Psychiatrists loved this drug for treatment of depression and so its popularity spread. Advertisements at the time touted the benefits of amphetamine for both men and women.

During World War II, soldiers and civilians in multiple countries were using this drug to stay awake (especially combat soldiers and pilots) or for weight loss. In fact, completely overlooking its abuse potential and addictiveness, the American Medical Association approved the advertising of amphetamines for weight loss in 1949, and sales took off even further. At the same time, more people were becoming dependent on amphetamines.

By 1960, as the drug’s harsh and harmful side effects began to be recognized, the drug began to be diverted to the illicit market. Still, both medical and non-medical use continued to grow.

The author of this report, Nicholas Rasmussen, PhD, summarizes why it was possible to initiate this epidemic, a conclusion that applies to other problematic drugs.

“When a drug is treated not only as a legal medicine but as a virtually harmless one, it is difficult to make a convincing case that the same drug is terribly harmful if used nonmedically.”

Has this ever happened with any other drug? The short answer is yes. Let’s take a look at a few examples.

Heroin and Cocaine

Heroin was introduced to the pharmaceutical market in the late 1890s. By 1900, opium, morphine, heroin and cocaine were all being sold in what were called “patent medicines.” Here’s some examples of the drugs sold around the turn of the century.

- Glyco-Heroin was produced by Smith as a cough sedative.

- Kendal Black Drops contained opium to be used for pain or as a sedative.

- Dr. Tucker’s Asthma inhaler contained cocaine.

- Lloyd Manufacturing Co. made cocaine drops for toothache pain.

- Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup for children may have eased their stomach pain but some children died of morphine overdoses.

The over-the-counter and pharmaceutical markets were completely uncontrolled in these early years. If a pharmacist, doctor or traveling salesman told you that a remedy was safe, you had no other information to counter those claims.

Between 1912 and 1920, these drugs were brought under a variety of legislative controls that limited the ways all these drugs could be dispensed.

Opioids

Until the mid-1990s, medical doctors were reluctant to prescribe opioid painkillers like morphine or hydrocodone because of the potential for abuse and addiction. But the mid-1990s was when Purdue Pharma in Boston began ramping up their innovative approach to marketing the time-release opioid formula OxyContin.

Purdue sales reps were instructed to tell doctors that this special time release formula made the drug unlikely to be abused and that use of the drug itself did not generally result in addiction. Doctors responded by prescribing this drug for all kinds of moderate-to-severe pain, not just those cases like cancer, end-of-life or serious accident pain where the benefits outweighed the risks. Knee pain, low back pain and other kinds of chronic pain began to be freely treated with addictive opioids for the first time.

Once again, an addictive substance was treated as harmless. And once again, the rapid spread of addiction was the result. When agencies and corporations tried to clamp down on prescribing, those who were already addicted reached for the heroin that was readily available from any drug dealer and much cheaper. The epidemic continued to spread.

What’s Next?

How about marijuana? As of this writing, marijuana has been legalized for medical use in 30 states and Washington, D.C. It’s currently legal for recreational use in nine states plus Washington, D.C. Legalizing this drug for recreational use is the perfect way to shout out, “It’s harmless!!”

Those who advocate the legalization of this drug downplay its addictive qualities, of course. But the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) recognizes its addictiveness. “Research suggests that between 9 and 30 percent of those who use marijuana may develop some degree of marijuana use disorder,” NIDA says on their website. But when a person begins to use this drug before the age of 18, they “are four to seven times more likely than adults to develop a marijuana use disorder.”

Is this the start of another situation of sweeping addiction? Unfortunately, the only way we can find out is to give it time.

For more than a century, it’s been unfair, dangerous and even fatal to ignore the addictiveness of one drug after another. You’d think we would have learned by now but this pattern has gone largely unobserved. Now you know about it. And now you have a greater awareness of the tactics that can lure unsuspecting people into addiction and you can fight back.

®

®