A First-Hand Account of The Empire of Pain

For me, and for the entire nation, it was vital that someone, somewhere, reported on the backstory of how America became the #1 consumer of opioid painkillers. And how we got into the situation, we’re in with skyrocketing drug overdoses, with opioids killing more people than any other drug. Someone has needed to tie all the threads of news reports and lawsuits together, link all the headlines and investigations, and compile everything into one massive report on the impact of the Sackler Dynasty. How in heaven’s name did this country get to the point that more than 100,000 of our citizens are dying of drug overdoses every year?

With his 2021 book, The Empire of Pain, Patrick Radden Keefe has completed a significant public service by telling this story in depth. As soon as I could, I got my hands on this book because I needed answers for all opioid-related phenomena I had been tracking for 15 years.

My exposure to this world of opioids started when I began working at a drug rehabilitation facility in 2006. I was new to this field and except for a couple of family members, had not had much direct contact with heavy drug use or addiction. Through my work at the rehab, I very quickly learned about the problem so many people were having with opioids. One woman told me her story about stealing prescription pads and writing her own scrip for opioids and then being arrested by the DEA as she sat in the drive-through of a pharmacy. Another fellow used a term I had never heard before: “doctor-shopping.” I had to ask someone what that meant.

In the next few years, I knew far more than I wanted to know about this topic. I learned about OxyContin, Percocet, Vicodin and morphine. I soon learned how a company in Connecticut called Purdue Pharma seemed to be right in the eye of this particular hurricane. I tried to look up their stock price and was baffled when I couldn’t find it till I discovered that they were privately owned. In 2007, I studied their $634.5 million settlement of a lawsuit filed by federal attorneys for “misbranding” OxyContin. At that time, I didn’t totally understand their role but they seemed to be a major player in this opioid situation.

I continued to research the subject after I left the rehab in 2009. Then, in 2010, I read a press release from Purdue Pharma about how they had developed a way to make OxyContin pills abuse-resistant. In that instant, my heart was filled with dread because I knew exactly what that was going to mean: hundreds of thousands or maybe millions of people were going to seek out sources of heroin when their pills could no longer be crushed or dissolved for abuse. I knew without a doubt that this migration to heroin was going to happen. I also know that because heroin potency is completely unpredictable, more people were going to start overdosing. While I was still working in and supporting this industry, there was nothing broadly effective I could do but wait for this new phenomenon to hit the headlines.

I was in a Minneapolis airport when I saw this news arrive on the front page of a local newspaper. I remember the picture of a tall, handsome young man in a football uniform featured in an article about how this high school student had inexplicably overdosed on heroin. The reporter was baffled because this wasn’t the kind of person anyone thought would OD on heroin. But I knew why he had. It knew it was going to take more years before the general public figured it out.

In the larger scheme of things, I was nobody. I wasn’t a scientist, a reporter, a regulator of drug policy or law enforcement. But I had known with absolute certainty that the reformulation of OxyContin would have this result. So why did I know what was going to happen when Purdue executives, the FDA and other people who should have known didn’t see it coming?

When Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic by Sam Quiñones was published in 2015, I devoured it avidly. I was ecstatic to see that the Purdue family figured prominently in this tale of how the opioid epidemic came to America. When I met Sam a few years later, all I could do was hug him and thank him. I thanked his wife, too, for supporting him in his journey of reporting and writing.

Fentanyl Arrives

I never saw the huge wave of fentanyl deaths coming until they began to hit the headlines in 2016. Earlier, in 2007, I’d tracked the arrival and quick departure of smallish quantities of illicit fentanyl between 2005 and 2007 that were mostly traced to a single lab in Toluca, Mexico. When that lab was shut down by Mexican law enforcement personnel, the fentanyl overdose deaths that had reached more than one thousand dropped to the level that could be reached with diverted pharmaceutical fentanyl alone.

When stories about large quantities of this illicitly-manufactured drug began showing up, I emailed Sam and asked him if his Xalisco contacts were talking about bringing fentanyl across the border. He said they weren’t.

As the fentanyl numbers kept going up and up, I could only keep writing informative articles to sound the alarm to as many people as possible. And I kept studying the problem, keeping tabs on Chinese manufacturers and dark websites that sold fentanyl or other illicit drugs that were labeled “research chemicals.” And then, I noted the next mutation of this industry: Chinese and other foreign pharmaceutical companies shipped precursor chemicals to Mexican cartels who used existing facilities to turn them into fentanyl and move the finished drug into the U.S. Since the cartels were already sophisticated manufacturing and distribution organizations, America faced an onslaught of this deadly drug that was unlike anything that had happened before.

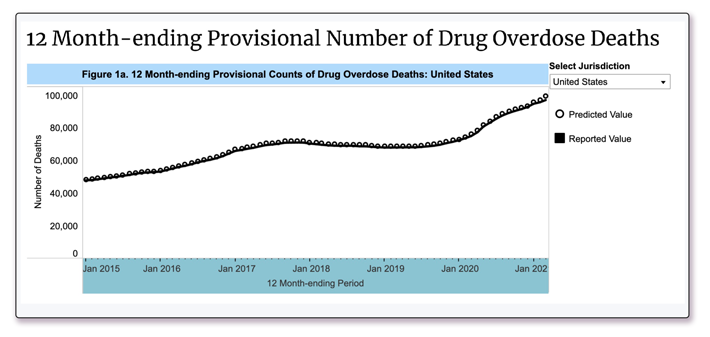

There’s a chart on the website of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that I began to haunt regularly. You can find this chart here. I’ve also included this chart as an image, below. The dots on the chart show the number of overdose deaths for the prior twelve months, updated monthly. It runs about eight months behind, so in November 2021, the latest dot on the chart shows the number of deaths for the twelve-month period ending March 2021. I watched this chart go steadily up for years. Then, in late 2017, the numbers began to decline. They continued to show modest decreases until July 2019. Soon after that, the COVID epidemic arrived, along with the closure of many rehabs and suspension of many services needed by those who are addicted. The chart has swung up sharply since then. Illicit fentanyl has been involved in massive numbers of these deaths.

The Constancy of Change

Nothing in this arena of life ever stays the same for very long. The drugs being used, the manufacturers or their methods of manufacture and the chemicals used, the traffickers who bring the drugs into America, the ways people abuse the drugs, the categories of people becoming addicted, the number overdosing and surviving, the number not surviving, the systems used at the street level to distribute the drugs, the legislation banning or permitting the drugs, trends in incarceration and the actions of the DEA and related law enforcement agencies—everything is always changing. To keep up with the subject, you have to be aware of every one of these aspects of the problem and more.

As I kept monitoring the situation. I saw Purdue Pharma’s star begin to dim and counted the lawsuits as they mounted. Hundreds, then thousands of lawsuits, amassed in an Ohio courtroom as multidistrict litigation, another new and very relevant term. Every month, more states, cities, unions or tribes added their lawsuits to the pile.

As the Sackler star dimmed even more, I began to see news articles about prestigious universities and museums in America and abroad removing the Sackler name from their institutions. One lofty organization after another began to reject or refund Sackler donations. Major magazines and newspapers began to connect the dots and publish exposés of the Sacklers’ underhanded marketing methods and their disastrous impacts.

In June 2018, a massive lawsuit filed by Maura Healy, Attorney General of Massachusetts, was made public. I read much of this document. I was astonished at the proof included in this filing of the disregard for human life and basic decency manifested by the Sackler family and Purdue executives.

Finally, Purdue Pharma was in bankruptcy. I read reports about how the Sackler family had been moving billions overseas so there was little left to distribute in a bankruptcy, but still, litigation directed at the company and the individual family members continued. It seemed that many people felt it necessary to impose every ounce of pain possible on this corporation and this family. Perhaps there was a general consensus that if there was to be any justice, the family needed to sacrifice as much as families who had lost loved ones.

I remembered that in 2007, the company (just who is the company?) had confessed to crimes and paid the fines. But then nothing changed. I really didn’t expect anything to change this time either.

Empire of Pain

Then, I heard about a new book by Patrick Radden Keefe titled Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty. Mr. Keefe chronicles the rise and fall of this dynasty in 434 pages of intensively researched text. For me and for many other people who have been touched by the opioid crisis in this country, it says what must be said about the authors of this disaster.

The Sacklers are not alone in making major contributions to the opioid crisis. Doctors who profited from running pill mills, pharmacists who never asked any questions about millions of pills being prescribed, executives of other pharmaceutical companies who only paid attention to company profits, government employees who failed to hold the Sacklers and Purdue Pharma responsible for the effects of their fraudulent marketing—there are many participants in this crisis.

It’s possible that healing completely from our burden of opioid abuse, addiction and overdoses will require holding each of these parties accountable for their contributions. In the meantime, those caught in the trap of addiction must be supported as they learn to live sober lives, while we educate our young to avoid the trap entirely.

Sources:

- https://samquinones.com/about/

- https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5729a1.htm

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

- https://www.mass.gov/files/documents/2019/01/31/Massachusetts%20AGO%20Amended%20Complaint%202019-01-31.pdf

- https://www.patrickraddenkeefe.com/

®

®